Hydrogen and the UK Market

Hydrogen, and humanity’s uses for it, have been around for a while. We use it to process fossil fuels, as a feedstock for fertiliser, and in large quantities in the food industry. However, the talk of hydrogen has expanded recently, from these more industrial uses into the power sector. Governments the world over have laid out ambitious plans to develop hydrogen economies and be the first to have a commanding position in this brave (and blue) new world. The UK is no exception, with hydrogen featuring prominently in the Prime Minister’s recently-announced 10-point plan.

Why are people talking about it so much now?

Hydrogen, when used as an energy source, emits no carbon-based greenhouse gases. Hydrogen can also be produced through zero-carbon (known as green hydrogen) or low-carbon (blue hydrogen) methods. Crucially, green (or low-carbon) hydrogen can also be used in other industries, helping to decarbonise areas that are difficult for renewable electricity options. Therefore, it is a key piece of the puzzle for tackling carbon emissions and bringing a country’s carbon footprint to net zero.

How can hydrogen become a key part of the UK economy?

The hydrogen economy boils down to two main problems: one of supply and one of demand. Both are still developing, and because of this both have been severely limited for decades, stuck waiting for the other to grow. However, momentum is building, and the UK is a market (and a country) with big opportunities on both sides.

The Question of Supply

The UK has decades of experience in the offshore oil and gas industries and has extensively explored and mapped its continental shelf. Refineries and depleted gas fields are plentiful around coastal areas and, though the focus is shifting from domestic production to natural gas imports, this infrastructure is still in good condition and concentrated around natural gas import hubs. This setting is a good opportunity for producing large amounts of hydrogen, which will be needed to start meaningful local decarbonisation.

Steam methane reformation (SMR) or autothermal reformation (ATR) are processes that produce a lot of hydrogen, using natural gas. Locating hydrogen plants at these pre-existing natural gas hubs gives 2 advantages: 1) depleted gas fields can be repurposed to store the CO2 emitted as a waste product, meaning this hydrogen becomes low-carbon; and 2) the hydrogen produced can be directly injected into the natural gas grid (as discussed later). SMR technology is decades old, works well, and has been used in UK refineries for a long time.

A second option is using renewable energy sources to generate hydrogen via electrolysis, the splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen. This can be done using electricity from renewable sources, such as solar and wind, and gives 2 benefits: 1) it generates truly green hydrogen with zero carbon emissions; and 2) it makes use of energy that can otherwise be wasted. Curtailment is a particular problem for renewable energy such as wind power, as the wind does not always blow when needed (and vice versa). Connecting renewable power to electrolysers allows generated electricity to be useful, regardless of whether the electricity grid needs it or not. With the UK Prime Minister announcing plans to quadruple offshore wind capacity to 40 GW by 2030, and competitive subsidy-free offshore wind on the horizon, this issue is likely to become even more pressing for investors and policymakers.

Some are challenging the need for a grid connection altogether, with projects such as Dolphyn designing offshore wind farms that only produce hydrogen. This recently received Government funding under the Low Carbon Hydrogen Production Fund, and their first demonstration plant is expected to be operational in 2023.

So, the opportunities for supply are there. Where can this new supply be used?

A Demanding Problem

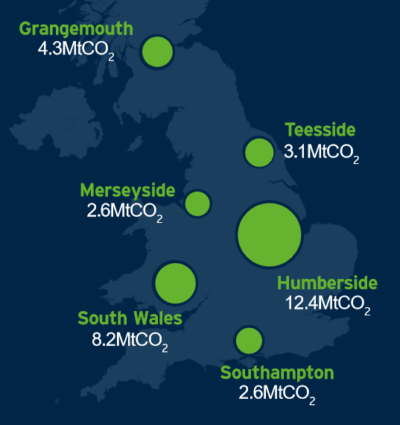

The UK’s industry is often loosely grouped into 6 industrial clusters: Humberside, South Wales, Grangemouth, Teesside, Merseyside, and Southampton. These clusters are on coastal or riverside areas, contain large varieties of industries, and are key targets for decarbonisation. The UK Government aims to have at least one low carbon industrial cluster by 2030, with at least one net-zero cluster by 2040. These are distant hopes, unless a large amount of low-carbon energy or energy carrier can be found.

Source: the UK Government’s Industrial Strategy, last updated September 2019

Enter hydrogen

An SMR or ATR plant provides a large centralised hydrogen source, which surrounding industries can use to reduce their emissions. Some industrial clusters, such as Merseyside and Humberside, are located close to depleted gas fields, giving the SMR or ATR plant a potential carbon sink. Many industries (such as the steel industry) are already experimenting with hydrogen-fired alternatives to their normal equipment, and umbrella projects have sprung up to co-ordinate these approaches across each cluster. The Government has supported this through various low-carbon hydrogen and carbon capture funding pots, with recipients including The Acorn Project in Aberdeenshire (supporting the Grangemouth cluster) and HyNet in North West England (Merseyside). The race to be the first net zero cluster is on.

Moving away from industry, the UK has an extensive and relatively modern natural gas network. This supplies around 84% of the nation’s homes for heating, in addition to a large number of gas engines and gas turbines across the country. Heat is an energy sector that has historically seen little decarbonisation progress in the UK, and so decarbonising this common network, by replacing some (or all) of this natural gas with green or low-carbon hydrogen, is an obvious step. This is both theoretically straightforward and needs very little new technology, and numerous projects are testing the gas grid’s capacity for change. As an example, HyDeploy started undertaking live testing at Keele University campus in 2019, having obtained the first exemption from the HSE to inject hydrogen into the grid – up to 20% of total gas grid volume. Meanwhile, H21 is a suite of projects exploring the conversion of the gas grid to 100% hydrogen. If proven safe and possible, and backed up with suitable subsidies (similar to biomethane injection), hydrogen injection could go a long way towards decarbonising the UK heat sector. Hydrogen-ready boilers and gas turbines are already coming onto the market, so this demand is unlikely to disappear in the short and medium terms.

A further use for hydrogen is in the mobility sector, another hard-to-decarbonise area that has seen little movement in recent years. Road transport in the UK accounted for approximately 21% of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2017, with the absolute amount actually increasing by 6% since 1990 (1). While early attempts at hydrogen mobility were overshadowed by airship-shaped disasters, recent efforts have been more successful, and a large variety of hydrogen vehicles are in development or already available.

Is hydrogen a competitive technology? It depends on what you want to transport where. Electric vehicles are firm favourites at passenger vehicle level, partly due to the range of consumer choice available and the more convenient recharging infrastructure. The key advantages of hydrogen (shorter refuelling times and smaller weight and space penalties with increasing range) are not as important here as its current disadvantages (cost and rare refuelling stations). However, the advantages are far more important for heavier vehicles like heavy goods vehicles and buses. Buses and some heavy goods vehicle fleets (for example, those servicing Energy from Waste plants) have predictable routes and a return-to-depot use pattern, making refuelling infrastructure relatively simple to build. London and Aberdeen already have demonstration fleets of hydrogen buses, with Liverpool and other cities following suit over the coming years.

Another option, where hydrogen can work alongside electric alternatives, is the train system. Electrification of lines is expensive, and while this is commercially viable for the busiest lines, it does not make as much sense for branch lines and less heavily-used parts of the network. For the most part these trains currently run on diesel, but they can be retrofitted (or built from new) to run on hydrogen. One example of this retrofitting approach is the Breeze train, developed by Alstom at their site in Widnes, which builds on their experience with the hydrogen-powered iLint in Europe. The first UK Breeze fleet is expected to be in operation by 2024 and, if successful, these trains could be rolled out across the country. Like buses, trains have set routes and predictable usage patterns, and refuelling stations would therefore be simple to link with hydrogen supplies.

Curiosity and Opportunity

In summary, a UK hydrogen economy is far from a far-off plan. Pre-existing strengths in renewables and oil and gas can support a strong domestic hydrogen supply, while net zero emissions targets will drive demand. This balance puts the UK in an almost unique position among the hydrogen frontrunners, as most focus only on one side of the equation. Australia will produce for export as its own demand is small, for example; Germany and Japan are facing the exact opposite problem and will need to import. Both approaches mean each country must trust that another will be able to supply it what it needs. Not so the UK: home-grown hydrogen production and domestic consumption could be linked, to create a self-sufficient and self-sustaining hydrogen economy.

This will be a delicate balancing act, as supply and demand grow from localised clusters to a mature network. Small change is already underway, but the time of pilot projects and demonstration scale is coming to an end. Pace needs to increase, and concrete developments begun, if the UK wants to meet its net zero obligations and become a hydrogen world leader. Some may wonder how reasonable such a big change may be in such a short time and whether there is appetite for this at the top. However, the Government seems convinced that hydrogen will have a key part to play in the future low carbon world – and refuses to let the UK be out of the limelight.